You’ve heard the word. You know the story.

Crisis.

The iconic, defining, definitive word of DC stories.

The word Crisis feels inseparable from the fabric of DC. It holds sway over its past, it informs its present, and it will certainly influence the future. You can’t think of DC and not think of Crisis at some point. The very idea of it has been bound to the very idea of DC that tightly.

And the response to the word and its invocation is intense as well. It comes with a lot of assumptions and baggage. Given that is the case, given it has become ubiquitous, inevitable, and all-pervading with DC itself, it’s worth discussing what has become of it. What has emerged from this focusing and this obsession over Crisis in DC? What has it led to?

The matter of Crisis must be unpacked, and that’s what we’re here to do.

Endless Escalation

By now, the problems of DC Comics and its Crisis storytelling ought to be evident and obvious. Consider the above page from Death Metal for instance.

Scott Snyder wants it to be a cool, slick, inviting party to rock out at in pure celebration of the past. And that’s cool! The art by Greg Capullo and colorist FCO very much fits that metal party vibe. It looks cool and conveys a sense of the ‘epic,’ depicting a wide tapestry and rich history. It feels like a party invite for the reader into the absurd realms of DC.

But then onto that gorgeous Greg Capullo artwork, on this great Double-Page Spread conveying scope and screaming Cool, you attach a billion droning caption boxes of text that seems to only drown out its impact. On and on the text goes about all these things you need to know, as it becomes a busy exposition overload in needlessly long, tedious fashion. It’s not just that there’s too many words; it’s that they’re all the wrong words here. They detract from the strength of Capullo’s terrific art. They tire you out, and you don’t end the page on the initial ‘Oh, cool, sick visuals,’ you instead end up exhausted. All it paints is a picture of endless, constant, tiresome escalations, as things keep getting Bigger and Badder, to almost parodic degree, and it doesn’t present a thrilling landscape at all that Capullo’s art seems to try to convey. It conveys one lost up its own ass in insular fashion.

If you ever have to write like that and do that much to do a basic sell of your event, you’ve evidently gone wrong somewhere. That absurdly busy page, stacked with text-boxes, is perhaps the best encapsulation of the issue here.

It’s constant escalation that means nothing. It’s an issue so obvious, so blaring, and so glaring, even Grant Morrison themselves pointed it out in a biting piss-take during 2020’s Green Lanterns: Blackstars series:

It’s a truth that feels inevitable and obvious to almost everyone with clarity, as even Morrison’s mockery here is one from a place of self-awareness. Morrison is well aware of their own complicity in this trend, particularly given their JLA was and still is the foundational model for that ‘every arc is massive and earth-shattering like an Event,’ and even their works since have somewhat contributed towards that endless parodic escalation of things.

It’s a truth that feels inevitable and obvious to almost everyone with clarity, as even Morrison’s mockery here is one from a place of self-awareness. Morrison is well aware of their own complicity in this trend, particularly given their JLA was and still is the foundational model for that ‘every arc is massive and earth-shattering like an Event,’ and even their works since have somewhat contributed towards that endless parodic escalation of things.

We have gone from ‘The Anti-Monitor, aka DC’s Galactus but Universes instead of Planets’ as The Big Bad to Alexander Luthor and Superboy Prime. We’ve gone from Darkseid and Mandrakk to Doctor Manhattan. Even Barbatos who was a more minor figure in Peter Milligan and Grant Morrison’s works became The Big Bad in a Crisis. And since then? We’ve kept it going.

We somehow got to ‘The Anti-Monitor’s Mom is The Big Bad’ as a serious idea as opposed to a joke comment. And then we got to The Batman Who Laughs, who in the stories is powered up to supergod status by Doctor Manhattan powers due to a Bruce Wayne/Doctor Manhattan amalgam from the Dark Multiverse. Now, if that sounds like a set of absolutely insane words, it’s because they are. That’s how we’ve been escalating. And now we have The Great Darkness and The Dark Army, collecting all of DC’s big event antagonists into an even more ever-escalating plot of multiversal disaster involving both ‘Pariah’ and Deathstroke.

Consider how we ever got to insane pages like this:

Which, the more you look at it, the more it feels like the comics equivalent and version of the Pepe Silvia meme:

These things have been derailed and lost sight of what matters most, or why people care about any of this. People keep doing stories all built around being Bigger, Badder, and Wilder than the last guy before them. They want to ‘top’ the past, and the only way they seem to be able to conceive of doing that is to try and raise the scope, scale, and bombast even higher, with even bigger nonsensical cosmic threats, as even louder and age old arguments about DC Comics are had.

But they forget none of that noise is why people ever cared or liked these stories. It was purely character. It was compelling character writing. And crucially, character not as representative or vehicle to wage insular fan arguments over nonsensical DC crap no one really cares about. It’s character writing rooted in real things, real feelings, real experiences and emotions, things beyond just the fabrics of DC comics publishing and its universal lore.

And the problem with these ever-escalating stories is they distract from that. The character(s) get lost in all that noise. What’s interesting about characters is watching them make choices, difficult choices, decisions that are hard, which require significant dramatic conflict, which carry a lot of weight and stakes, and have consequences that will be felt. It’s why people love, say, All-Star Superman or Watchmen, despite those being radically different books. They’re not tirades or fan arguments insular to the superhero. No, instead they strip away all that noise and tell really strong character-focused, thematically-driven genre stories with these figures that speak to larger struggles, realities, and universal feelings.

What this mode of endlessly escalating event storytelling that has been so bound up with the word ‘Crisis’ does is present the veneer of character and choice- whilst offering none. The characters get ‘choices’ in these books, sure, but they’re not really choices. They’re obvious, easy, predictable things that need to happen to serve and facilitate the plot. They’re reactions the characters need to have in a reactive manner to make the event ‘work.’ They carry the veneer of ‘challenge’ and ‘dramatic conflict’ but really have none. And neither does the decision/choice, as the consequence is just some other aspect of meaningless plot or ‘set-up’ for the next big event comic that’ll repeat all this.

Everything feeds the next Big Thing, and keeps the machine running, and it’s all Stuff Happens comics that you’ll forget by the time the next one rolls around, because that’s how it works, and that’s how they get you to pay up. It’s cheap, hollow, and it does a disservice to both the characters and the readers who hope to read them.

(The Absence Of) Dramatic Conflict and Real Choices

If you’ve read this far, you’ve likely wondered at least once ‘Why no mention of Identity Crisis, which came before Infinite Crisis? And why no Heroes In Crisis?’, and that’s understandable. They’ve been excluded up until this moment because this is precisely where they make the most sense to discuss.

We’ve discussed the importance and necessity of Crisis stories moving away from the ever-increasing escalation featuring ever larger supreme antagonists like That One Alan Moore OC, This Riff On An Alan Moore OC, or Anti-Monitor’s Uncle. There’s gotta be a different approach to ‘Crisis’ comics that takes a break from all that mad mayhem and increasingly bombastic reality-breaking affair with the whole multiverse on the cusp of redefinition every Wednesday.

And that alternative has historically been represented by the mode in which these two Crisis books work and operate. Brad Meltzer and Rags Morales’ Identity Crisis was technically speaking the first real ‘Crisis’ comic of the modern era, and one overseen and approved by Dan Didio himself. It would lay the groundwork that’d be picked up on and become story for Johns’ Infinite Crisis and even 52. It was the beginning of the Didio ‘Crisis’ era of modern DC comics, being among the first things Didio oversaw when he came to the Publisher under the tutelage of Paul Levitz.

And if Identity Crisis was a shock-wave that led to a Geoff Johns event that was all Fan Arguments staged as comics, then Tom King and Clay Mann’s Heroes In Crisis was a different beast. Heroes In Crisis followed on from Johns’ DC Rebirth, and rather than preceding the Fan Argument Comics, it would be a response to some of the ideas in those comics. Both books are quite different, evidently, but at the same time they have more in common than not. For one, Brad Meltzer is a direct inspiration and influence for Tom King, and both Meltzer and King share a desire to take a novelistic approach that feels a bit different from other Crisis attempts. Plus, both are Watchmen-inspired comics to the bone- murder mystery dramas steeped in the troubling secrets, coverups, and failures of the leading heroes and the superhero community. If Identity Crisis merely seemed to try and (in juvenile fashion) mimic the trappings of a ‘mature’ superhero comic like Watchmen, Heroes In Crisis would try to much more actively take from its form as well, deploying King’s love of 9-panel grids, all topped off with a whole blatant ‘I did it 35 minutes ago’ reference.

Both were comics that weren’t about the end of the world, but were human dramas about the community and struggles and pain of these people within them, and how they dealt with that. They both hinged around and focused on choices. Characters made notable, messy choices and decisions that had clear repercussions in the story, and also carried many implications. Both stories actively problematized and brought a discomfort to their superheroic cast of characters and their communities.

But the problem is…both were deeply, deeply poor works. Both comics are, for instance, laced with really poor handling of the female characters. Identity Crisis in particular, given its whole premise is ‘What if the Justice League dealt with a case of horrible sexual assault within their community?’, with the story being the worst possible answer to that question. It’s hard to look at the book and not see the almost raging, bone-deep misogyny in that book, with horrid evocation and shock-value deployment of Sexual Assault. But even beyond that, Identity Crisis is a deeply poor mystery that opts for said misogyny in its revelations and resolution, when doing so actively breaks its mystery completely and totally beyond any sense or believability. It’s a book that has the choice between having a workable mystery or being misogynistic, and it opts for the latter. When it reveals that Jean Loring, the Atom’s Wife, has been The Secret Mystery Bad Guy All Along, it’s baffling. Its a book whose characterizations of its cast operate in shallow caricature, its idea of human drama deeply juvenile and insipid, and generally feeling like the worst kind of attempt by out of touch try-hard guys to say ‘Comics are Mature now, man!’.

It’s a book that understands that character choices, decisions, and agency are interesting, and that human drama is compelling. It’s just that the only way it can seem to do that and manifest that is in awful, rubbish stories involving women’s rape, coverups and mind-wipes that screw with people’s memories. It’s all shock with no real substance. It’s an empty void of a book with no soul. It’s hollow mimicry without any grasp or understanding, and it brings is ruin. For to confuse shock with story is to not know story at all. The end result is something that thinks it is deliberately uncomfortable in the literary sense, but in truth is just repulsive rubbish with little to say. There’s nothing up on offer here, and no humanity to hold onto. It’s an idiot’s idea of Prestige TV and Alan Moore comics.

Heroes In Crisis on the other hand is less of a mess, but still deeply stupid. Its handling of its women in contrast to the men, from Batgirl to the way Mann’s pages at times present Lois Lane in a way that takes away from what the story wants to be about, is poor. King’s work in general has tended to write women in a set of noir archetypes, and nowhere is the limitation and the flaw of that more clear than here. But even beyond that, while trying to make a comic about mental health and mental illness and how ‘just go to therapy’ isn’t a fix, and how the heroes absolutely bungle and mess up this therapy program isn’t inherently bad, the end result here does feel like the worst possible version of it.

Worse is the fact that King had talked about how the story’s inception was rooted in School Shootings of America, and thinking about what happens when spaces meant to be sacred and safe are violated like that and covered in violence. Here’s King himself speaking on that matter for press, as reported by Polygon:

We already knew that Heroes in Crisis would be a murder mystery, but at San Diego Comic-Con King revealed the scale of that mystery. The inciting moment won’t just be a murder, but a mass shooting.

“It starts with something we see everyday in America,” King told reporters in San Diego, “Something I saw when I was overseas and I never thought would come here, but it’s here and it’s fucking everywhere. And it starts with a massacre at Sanctuary — in this space, in this safe place, in this place that Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman dedicated their lives to keeping safe — a dozen heroes are killed and they don’t know who killed them.”

Polygon asked King how the idea of using a mass shooting in the story came about, and his answer was simple. His youngest child was about to enter kindergarten, and he’d realized that among all the usual fears about how his son would fit in with his classmates, was the fear that he’d be harmed by a school shooter.

“And because I have a fucked up job, I was like, ‘Oh, that’s a great idea for a story,’” King said. “That’s how I was thinking of Sanctuary. It’s a safe zone; it is someplace that you can’t violate. And that would happen there, there would be a massacre in the one place that that shouldn’t happen. That’s where the idea came from.”

And the end result of that becomes a story that feels like it evokes all the worst parts of those real life School Shootings themselves, wherein the real victims who suffered and died in the tragedy are reduced to small tiny boxes and testimonies to punctuate their tragedy, to serve their role as The Victims and little else, while Wally West who is behind these deaths is given central focus as the leading man and star with all the interiority and complex motivations in the world. Wally West becomes the White School Shooter figure, the monster media covers ad nauseum and tries to paint as a sympathetic figure to ‘understand’ while reducing the actual victims to footnotes.

There are character choices and decisions and human drama, but they’re ill-considered ones that feel carelessly implemented without the meaning and implications really worked though.

Perhaps the only real arena in which Heroes In Crisis works is its response/counter-examination of Wally West’s horrifying existence. Johns in Rebirth makes the pretense that this man who had lost all his history, his entire life and all his achievements, everything he ever did, his wife, the love of his life, his kids, none of that existing…would seemingly be okay. That he could and would be the symbol of Hope and Optimism. A symbol, not a man or a real person with real feelings and emotions. Even in Rebirth books, when Wally eventually meets Superman (who has his family despite the reality shenanigans) he just gets a ‘Well, it’s worked out for me! Hope it does for you man, see ya!’ rather than any measure of real comfort.

What would losing everything you ever were, ever did, ever had do to you? What would your wife, the love of your life not even knowing you or recognizing you do to you? What would losing your kids do to your mental state? How would having everything you ever did undone hurt you? And how would that all hit you even more when people grasped your shoulder and you that you were ‘Hope’ and people admired your ‘Optimism’ and ‘Heroism,’ when you didn’t want that, you just wanted your family, your love, and your life back?

What happens when people prop you up and turn you into a symbol of Hope like that, without caring for or considering your feelings and wrecked emotional state? How would it actually feel to be a legacy hero whose very legacy had been completely erased?

These are the questions Heroes In Crisis delves into with its Wally West, and it tries to be emotionally honest about them, suggesting that the shallow ‘hope’ spiels of Rebirth are emotionally dishonest. And that we should consider the feelings and emotional realities of Wally West as a character, as a person, rather than prop him up as some abstract symbol, because that’s not what made him fun or interesting. Barry was the symbol. Wally was the man. And it’s not wrong on this front. The problem is just that given the inception and nature of the story, and the eventual choices it makes, where it takes Wally become deeply poor decision-making. And not ‘poor decision-making’ in a dramatically compelling, deliberate fashion, but poor decisions as in ‘This does not work and it really needed reconsidering and more thought.’

It’s all the worst and most careless parts of Tom King’s work writ large, particularly with its framing that casts Wally West in a role akin to a White School Shooter. And when you’ve ended up there, with a sentence like that, you know things have gone irrevocably wrong. It’s a problem that tracks with the brand of Whiteness and emphasis on White men of violence that is characteristic of ex-CIA agent Tom King’s work. And its essential failure is perhaps best captured here, in a brutal honesty that may be hard to find elsewhere. It’s a book bound to King’s particular background, with the concept of ‘Sanctuary’ being informed by the mental health/help/therapy situation of American veterans and military men who are dealing with PTSD, and how the whole thing is a disastrous mess. It’s why despite many fans pinning all the failings on Dan Didio or Editorial, the idea that the book isn’t really King’s is deeply dishonest and misled. No, the very concept was bound to Mass Shootings in America, particularly in Safe Spaces like schools. That is the way the book is to be read, for it is its essence, and it is indivisible from King’s own troubling background and baggage.

In the end, these are really poor comics. They focus upon character choices and decisions, they understand that agency is interesting, they understand that you need dramatic conflict, with the choices having to be spiky and ones that surprise and have impact, as opposed to being obvious or ‘easy’. But they have no idea how to conceptualize that beyond tired, poor frameworks that are in their own ways just as obvious and easy. Rather than spotlighting the humanity and complexity of these characters, the works devolve them into a different kind of caricature.

And that’s a shame, that these two are the only big ‘alternative’ Crisis stories. Mystery Dramas and thrillers are great, and set in a superhero universe? Even better. And rooted in strong character choices/decision-making and messiness and complexity of these figures? Even better! The basic building blocks of this approach, rooted in Moore’s Watchmen, are very good. It’s an approach suited to making some very strong character-driven comics. But we haven’t done it yet. We haven’t had a proper slam dunk, a really good one that hits like a home run. We’ve instead been stuck with these poor failures of the mode, with the stink of them putting off anyone from doing something in this mode, and veering even harder into the more commercially saleable and cynical Escalation/Bombast mode.

And because of that, Crisis is a broken story framework and word in DC’s context. It distracts from that which is essentially great about these characters, it reduces them when it need not, and the whole affair tires and exhausts in ways you really wish it did not.

Another Way

But perhaps it need not be like that. Perhaps there are other ways to do Crisis-esque storytelling, and if Crisis began by riffing upon and being inspired by a Marvel classic like The Galactus Saga, then lessons can be learnt from modern Marvel classics, too. There’s other paths to take to pursue a Crisis, and the hint lies very well in what Scott Snyder himself tried to draw upon during his Justice League/Metal tenure- Jonathan Hickman’s Marvel Saga.

Hickman is a self-proclaimed lifelong DC hardcore, with Grant Morrison being his all-time favorite comics writer. And it shows. His entire Avengers Saga is essentially a ‘What If?’ story exploring Crisis stories and Crisis mythology, with Multiversal Collapse and Cosmic Death as grand, operatic character drama, as you follow the various Marvel characters and their big, bold, wild decisions and choices in the face of things. What does Tony Stark do? What does Steve Rogers do? What decision does T’Challa make? What is Namor’s choice? And what of Reed Richards? On and on. Hickman understands that cosmic abstract nonsense and ‘events/plot’ aren’t what’s compelling or interesting. It’s the decisions and choices characters make in those wild frameworks. Particularly the wild, spiky, charged decisions that won’t get claps or fan cheers, and might reveal their flaws and messiness as people.

The questions it was asking weren’t meaningless, empty broad-strokes nothingburgers like ‘Can X Character Or Team Be/Represent Hope™/Optimism™? Can they be Heroes and Light and Fight The Villains and Darkness?’. It was not just going ‘Heroes! Villain! Punch Explosion!’ with cheap and empty fanservice. It wasn’t coddling, comfortable stuff resistant to challenging characters. Because, to quote the newly appointed co-CEO of DC Studios and his new mission statement:

“You can’t be telling the same ‘good guy, bad guy, giant thing in the sky, good guys win’ story again,” Gunn said. “You need to tell stories that are more morally complex. You need to tell stories that don’t just pretend to be different genres, but actually are different genres.”

Instead it was asking much more specific questions, putting characters in very specific situations or scenarios that pushed them and pulled them apart, wherein characters vested with great power had to make big, sweeping, powerful choices with that power, and each choice made would reveal their essence and true nature, because it all came at a price. And each choice would have its own array of consequences and impact that the characters could not escape and reckon with. It wasn’t easy. It was hard. It was difficult. And that’s what made it rich and interesting drama, something worth following and reading about.

It’s why when the whole Avengers saga built to his grand event Secret Wars, with Alex Ross covers leaning hard on that Crisis-esque imagery and iconography, it all meant something. It was all rooted in character, and was an outgrowth of character, in a way Snyder’s attempt at DC never really was, often losing that for extra bombast and plot distractions.

But given we are trying to move beyond the tales of multiversal death and reality death and Bigger, Badder Cosmic Disasters, there’s an alternative model. One proposed by Hickman himself, moving past his own prior Marvel work, and just as rooted in his DC influences and sensibilities.

House Of X and Powers Of X – each 6 issues but collectively a 12 issue maxi-series- is perhaps the best modern ‘event’ comic since Secret Wars, and also in essence the best ‘Crisis’ story without being one. It’s a tale of endless cosmic rewrites/repeats/reboots of the superhero reality, like a billion Crisis comics- but it’s all rooted in character, in Moira MacTaggert and her choices, her specific decisions in each life, and her motives as informed by her experiences. The cosmic is the personal, the Crisis is the internal, and it’s rooted in a story of people. It’s rooted in Moira’s views and ideology, how it relates to her mutanthood and view of being one, how she relates to marginalization and her kin, and who she wants to be. The creative team of Jonathan Hickman, Pepe Larraz, and R.B Silva understand that people and character, their ideologies, their decisions and choices as informed by them, that’s what is interesting. Moira doesn’t always make the ‘obvious’ or ‘easy’ choices, and she makes poor choices and messes up, and that’s precisely what is compelling. It adds drama and conflict and gives you things to chew on.

Even its central starting point is ‘Charles Xavier and Magneto have made a decision together, and will now change mutantdom forever.’ It’s one that alters and radically shifts the definition and approach of X-Men comics, as they go from a people seeking acceptance from humanity as an Institute to a Nation of super-humans far beyond asking for acceptance. While previously attempted, the way in which it is done and framed, with even mutant languages being made and an actual culture being formed, these are all meaningful ideas. They’re about something, something tangible and real as opposed to insular Crisis nonsense. And it is all firmly rooted in choices. Choices like how Xavier and Magneto keep secrets that will eventually blow up down the road, or how Moira’s plotting and making choices that will lead to explosive turn of events down the road, so on and so forth. Even choices like ‘Apocalypse becomes a mentor figure working on the newly formed Krakoa, working with Xavier and Magneto’ aren’t obvious choices and offer great dramatic conflict and surprise. They give you tons of rich potential character dynamics and interplay by which to mold story. And easy/cheap gimmicks like character deaths are thrown out the window, as the X-Men are effectively made immortal, and death and how people approach death is re-framed to yield wholly fresh new stories, with a well of possibilities opening up.

And more than anything else, HoXPoX was the story of something being built, something created, of mutants pro-actively creating and constructing something from nothing, and the drama, the thrills and conflicts and surprises and fun of that in a big, wild, sci-fi genre fiction context. It was not another ‘Reacting to Cosmic Disaster’ plot. And that feels like a useful model and mode to consider moving forward, as something that could be learnt from. But of course, it’s not the only model or way to tell powerful genre stories with real ideas, meaningful dramatic conflicts, engaging character dynamics and genuinely surprising choices with challenge. It’s just one model or way out of a billion.

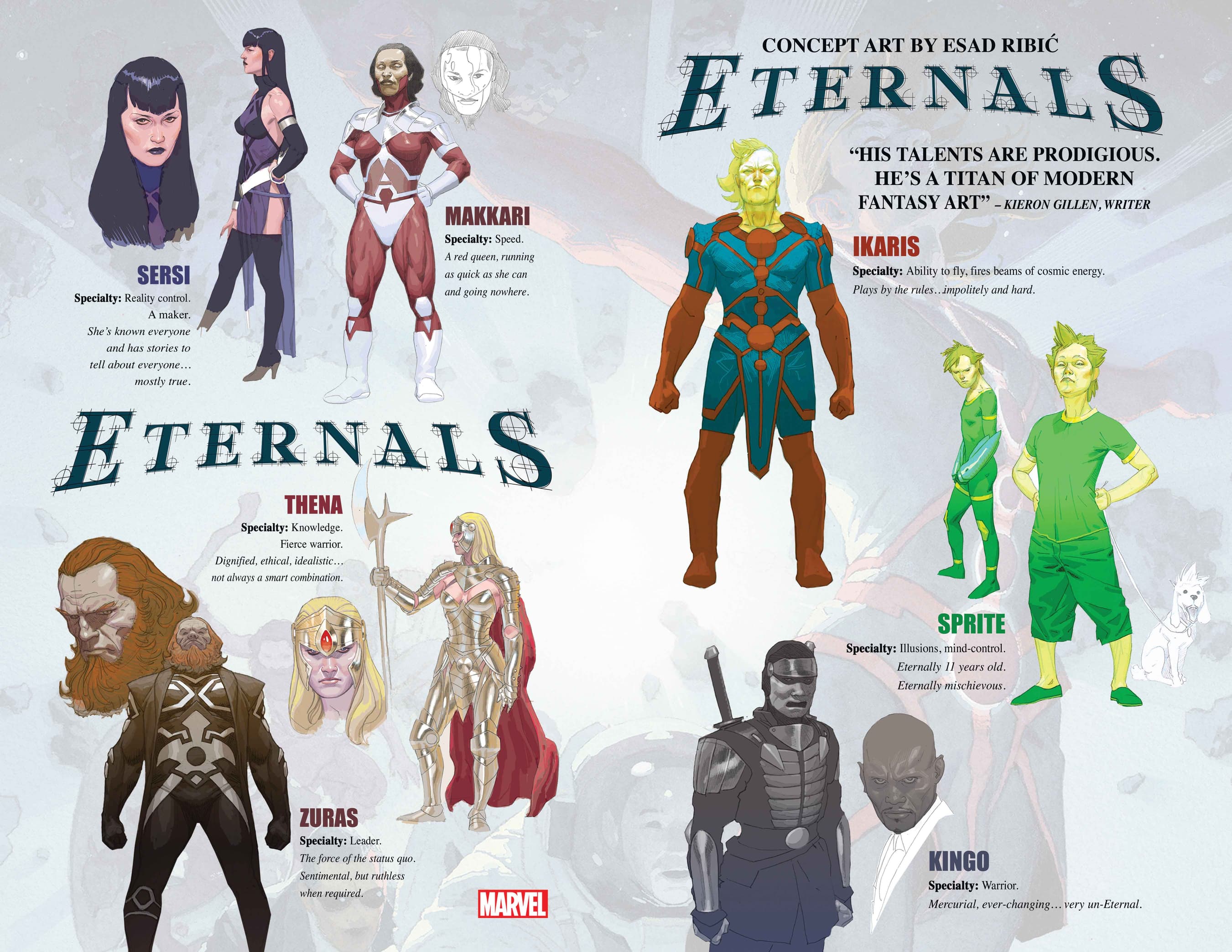

Consider, for instance the recent Eternals revival by Kieron Gillen and Esad Ribic. Gillen is working with a roster and super-society of beings on the scale of The Justice League, if not bigger, who are played along the lines of ‘Superheroes as Mythology’ which DC comics and its creators love so much. They are cyclical characters and figures who have numerous ‘reboots’ and ‘restarts’ and that’s built into the story and played with in the context of genuine science-fiction ideas and storytelling. Emphasis is played on dramatic character choices or decisions, as stories can range from a rigged election and the Eternals choosing to vote in Thanos as their President, essentially, to centering on Asimov-esque laws/principles that guide Eternal existence. Numerous past stories or ‘continuity’ messes are re-framed through an explicitly political lens of ideology, granted newly coherent meaning and purpose.

The Eternals are humanized through the understanding that every time they die and return back to life- there is a cost, a price that is paid. Each time they return to life, a human life is gone. One life for another. And this suddenly colors their entire past and history, their every choice or action without a care about death. And it will now forever color their future, and every Eternal reacts to the knowledge in a specific way, as they come to understand who they are, who they’ve been, and who they want to be. And then they make dramatic decisions stemming from that understanding, which opens up a whole world of fresh storytelling possibilities. Again, these are real science-fiction ideas with weight, rooted in character and character choices. It’s what so many big DC stories have lacked so profoundly for ages now. One need not even like or be a fan of HoXPoX or Eternals to be able to tell the difference between works with an actual honest-to-god high concept and real sci-fi ideas as opposed to the regular hollow recycling gimmicks. And it helps that writers like Hickman and Gillen are very deliberate formalists, with a clear eye and ambition for how to vary rhythm in their issues and how controlled Aesthetic Pages (‘Data Pages’ as X-readership calls them) can alter a reading and the experience. There’s a care and consideration combined with ambitious ideas here that is non-existent in most of these DC efforts. A writer like Gillen is able to lean into culture, ritual, and faith in the context of the Eternals and their many tribes, and what you have is something genuinely compelling to read and experience. It’s how and why you can get the culmination of his story in a sensational event like Judgement Day.

But again, this is just one example of many, much like HoXPoX, which should inspire new work rather than plain mimicry, which, as we’ve discussed, is a major problem. People doing poor mimicry is a good part of why we’re in this mess to begin with, whether it’s Watchmen or Crisis. The fact of the matter however is that we don’t need to be where we are. There are a plethora of ways to do this. There really is no limit. All you need are real ideas that challenge and question the characters and their work in dramatically compelling ways, rather than coddle the readership to stagnate. And crucially, you need writers with a clear, standout voice and vision who can actually execute said ideas, who have the craft and skill to back up those ideas and pull them off. You need more than the fanboys who can recite Superman or Flash’s Social Security Number from memory or win trivia nights. You need more than people obsessively blathering on about the sacred sanctity of a character or IP and ‘how they should be’ and continuity nonsense.

You need writers with a real idiosyncratic perspective, who’re allowed to take these big gigantic enterprises and use them for bold, ambitious personal expression that speaks to something real and moves us. It’s what distinguishes the Hickmans and Gillens from the average workman writer. It’s what distinguishes a Morrison from the rest of the pack. The past doesn’t exist to be rehashed endlessly, but learnt from to genuinely surprise us. The point isn’t to do things that make people point and go ‘Hey, I know that easter egg! I got that reference!’ like a Cinemasins viewer, but to make them point and go ‘I don’t think I’ve seen that before. Now that’s interesting! Huh!’. That’s what true writers do, they find ways to surprise you and move you. And even if they fail, perhaps they’ll fail interestingly, in ways that are worth reading and engaging with, as opposed to failing while just recycling. We do not have to settle for these tiresome gimmick books that none of us will remember a few months from now. Crisis doesn’t have be like this or mean what it does. It need not be something that makes people sigh or tires them out or makes them weary. Crisis should open up a well of possibilities, rather than just be an insular hellhole of pointless repetition and recycling. It’s time to make new music rather than just do cover songs.

Perhaps it’s time we did that and actually moved forward to somewhere useful, as opposed to just relying on cheap and easy nostalgic recreations wherein The Anti-Monitor’s Second Cousin and Grandpa both showed up and possessed Psycho Pirate, Lex Luthor, and That Alan Moore Character to wreak havoc or what have you.

It’s time we stopped re-litigating arguments and debates about moving forward in comics that are all too happy to indulge in moving backwards. It’s time we got beyond the Crisises of the past- to go somewhere new, to make something new. If there are to be more Crisis comics in the future, and there will be, that’s just the nature of this business and enterprise, perhaps they could dare to actually move forward, be bold, be daring, and try to imagine something worthwhile. Because folks? We really do deserve that.

We deserve better than all this.

Leave a Reply